At first glance, Catherine Bull’s “First Day in Sydney, 1992” is both memoir and snapshot, or perhaps a memoir within a snapshot. The breathless recollection, delivered without punctuation, evokes the conversational quality of listening to the account of a recent (or not-so-recent) holiday – but with a twist.

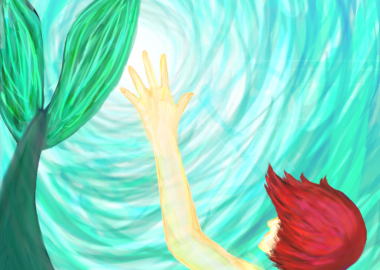

“It’s Bondi Beach and the boys/are building a sand sculpture this really/amazing merman” – two and a half lines of opening that provide a cadence of chatty consonance and assonance – set the tone for a visual depiction of youth, of longing, and of transience. “[A]lthough, really, Valerie’s in a bikini so/the rest of us are moot anyway….” Irony, depicted as comparison, provides a narrative distance that allows the reader to step in the scene of the Australian-sandcastle-building endeavor.

There are two interesting additional narrative spaces created in this poem. The first-person point of view provides an immediacy that we discover, later on in the poem, is actually the persistent aspects of memory rather than reportage. This is most obvious when the narrator recalls in shimmering detail her various crushes and opinions on her male friends –

Joe Sze is hot

I like Rhett he’s a little Southern

and Christian Brasier who threw my book bag

down the hall every single day

…. only to discover, beyond the title’s timestamp of 1992, that the narrative has moved swiftly ahead: “he’s in real estate/in Southern California now/I googled him once.”

Also within the poem’s seemingly breezy construction is the idea of the photograph, or rather the act of photography – “they pose in front of the merman/with their bare chests which I’ve never seen on them before/and we take pictures.” In the poem’s closing lines, “they jump up and down on the merman/and destroy it entirely/and we take pictures of that too.”

What is the significance of taking pictures and bookending a poem’s action with visual signposts and then elevating the visual to the linguistic, to the permanency of printed words? The reader can take the poem on the level of a painting, an image, a scene. But the reader can also look to the constructed and deconstructed sands of emotion in the work, to the shifting tides of nascent sexuality and attraction, to the kinetic quality of the spoken retelling and impressions captured in an instant.

For me, the piece is really about capturing what cannot be captured – but poetry is perhaps the form that comes closest to coalescing memory into myth. Still, the subjective ensures that each retelling is unique, and has its own talismans and trials that demand our immediate focus and understanding as readers and writers — “but it’s too late/for courage they pose in front of the merman.”

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://minotaursspotlight.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/rose_koch_133.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Rosemarie Koch earned her MFA in Poetry from Arcadia University in 2013 – the culmination of a lifelong dream. For her, poetry is an art form that crosses all forms, and is also a great source of joy – both reading it and writing it. She has recited Hopkins’ “Windhover” at many poetic and non-poetic gatherings, regards William Blake and Emily Dickinson as close personal friends, and finds poetry in everything she hears and sees. Her work with Minotaur’s Spotlight is an extension of her love of verse. [/author_info] [/author]