By Michele Reale

You should have just asked the mosquito.

—14th Dalai Lama

Reading Cameron Conaway’s biography, one would not imagine him to be the author of a book of poetry about the dreaded disease, malaria, but there you have it; he is. Conaway is a man of the world, a man who wears many hats: Executive Director at GoodMenProject.com, a former MMA fighter (!) , advisory board member of “Slavery Today: A Multidisciplinary Journal of Human Trafficking Solutions” and an award-winning poet. I mention the breadth of Conaway’s experience to show his deep involvement in life in general, and social issues in particular, as well as his ability to engage these issues in his writing—which makes some issues (well, malaria, for one) highly interesting and at the same time relevant.

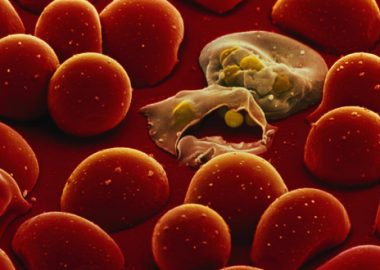

When we think of “malaria,” if in fact, we think of it at all, mosquitoes come to mind. What also comes to mind is that fact that most of us who will be reading this short review will not have to worry about it, living, as most of us do, in the developed and industrialized world. But that is not true for so many. Conaway opens up a world of the infected, those treating them, the politics of disease (read dis-ease) and a witness to the suffering of the afflicted and does so with poems that are varied in length and form, but all having the intensity of someone on the front lines—engaged, caring and witnessing.

Cameron is incredibly adept at getting at the heart of the matter quite quickly, showing us the indiscriminate nature of the infected insect. Babies, old people, the educated, the happy are all equally at risk if the insect sets its sights on your skin. In “Silence, Anopheles” the haunting refrain is “It’s risky business,” which becomes a sort of mantra into the world of a global disease, where danger lurks everywhere:

Risky when you’re born

on water and capricious cloudscapes

shape whether sun lets leaves

bleed their liquid shadow blankets

into marshes or mangrove swamps

or hoof prints or rice fields or kingdoms

of ditches.

Punctuated throughout the collection are facts, bits of fable and official pronouncements on the disease:

“Malaria in pregnancy causes 200, 000 still births in Africa” —title of an article in Ghana Web, 12 June 2009

The poem “Still born” follows:

At cock’s crow she presses the pink

of his unformed lips to her breast.

Soon the dead will have another

Birthday, and she will tell him stories.

What Conaway has accomplished in this collection is nothing short of a service to humanity in bringing the dreaded disease, still rampant in so many places on the globe, into the light of day and doing so in such an evocative, varied and informative way. It would be difficult to imagine anyone remaining unmoved after reading these poems. In the final poem, set in prose, “Landscape,” Conaway acknowledges his relative safety form malaria and the unfortunate places in which it lurks, but he is never, ever emotionally or intellectually remote:

Even here where I am if I get bit and do get malaria, I’ll be okay because of where I come from and who I know and what is already in my system. I am here, but I am not really here as the locals are, and as much as I try I never will be. All I can think about right now as the rain stings my head and my feet sink deeper is how somewhere out there or up there or down there or over there and definitely later on the hush will be accompanied by a hum so gentle as to be imperceptible, and this hum is so gentle that this place is still indefensible against it after all these years of days.

Michelle Reale is an Assistant Professor Arcadia University in the suburbs of Philadelphia. Her work has appeared in a wide variety of publications both in print and online, including Nano Fiction, Smokelong Quarterly, Pank, Gargoyle, The Pedestal, elimae, JMWW and others. Her work was included in Dzanc’s 2011 Best of the Web Anthology. She is the author of five collections of short fiction and prose poems. She has been twice nominated for a Pushcart Prize. She conducts ethnography among African refugees in Sicily and blogs about some of those experiences concerning immigration and Migration and Social Justice in the Sicilian context at www.sempresicilia.wordpress.com.

Michelle Reale is an Assistant Professor Arcadia University in the suburbs of Philadelphia. Her work has appeared in a wide variety of publications both in print and online, including Nano Fiction, Smokelong Quarterly, Pank, Gargoyle, The Pedestal, elimae, JMWW and others. Her work was included in Dzanc’s 2011 Best of the Web Anthology. She is the author of five collections of short fiction and prose poems. She has been twice nominated for a Pushcart Prize. She conducts ethnography among African refugees in Sicily and blogs about some of those experiences concerning immigration and Migration and Social Justice in the Sicilian context at www.sempresicilia.wordpress.com.