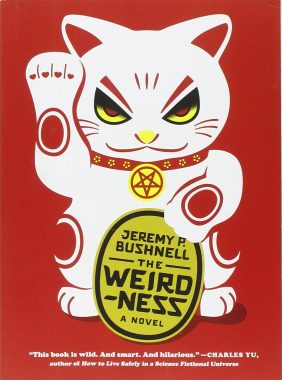

Have you ever played “don’t let the balloon touch the ground?” Surely you’ve played it at a birthday party when you were a kid, or perhaps while drunk at your cousin’s country-chic wedding. The goal is to continually bat an air-filled balloon around and try to never let it touch the floor no matter the unpredictable direction it might have taken or how far it gets away from you. This game is what I imagine Jeremy Bushnell had in mind as he wrote The Weirdness. As soon as you think you understand the story line, the balloon gets kicked back into the air and all bets are off. An aptly named novel, The Weirdness follows self-deprecating protagonist Billy Ridgeway as he navigates his lackluster life, and is unexpectedly propositioned by Satan to run an errand of sorts. As one might assume, Satan has a few other things in mind aside from what he told Billy. I won’t get into much else that happens in the book because you might think I’m making it up. Just read it.

Normally I don’t enjoy when writers write about writers. Having evaluated many manuscripts with a writer as a main character, I find they’re often simply everything the author thought about himself but couldn’t admit to in a more direct manner. I’ve perhaps grown a bit weary of it. But Jeremy Bushnell surprised me with his extremely astute and somewhat sardonic approach to crafting Billy. Billy is a writer, accurately portrayed with a hefty self-doubt, balanced with a loose grasp on his personal pipe dreams. But he also understands some of the more ridiculous aspects of some writers and the literary community. He’s an entertaining critic, observing and sometimes lightly eye-rolling at the aloof, elitist mien of many creative types and Delphic hopefuls who try desperately to smash vagueness and deep meaning into the same package. Bushnell’s awareness and portrayal of this part of literary and artistic culture is bold and hilarious at times, while staying well behind the lines of being outright insulting. Although it’s actually a very small part of things, it’s a great characterization element and addition to the story.

The real hero of this book is the tone, however. Bushnell nails an informal, somewhat grumpy voice that’s both humorous and earnest. It’s reminiscent of Terry Pratchett to me. It knows it’s supposed to come off a certain way and adhere to certain rules, but it just can’t seem to drum up enough effort to care. It turns usually-heavy subjects into things that are noncommittal and amusing, but still maintains a great intelligence and self-awareness. It’s the meat and potatoes of what made this book so fun for me to read. For example, this excerpt from Billy and Lucifer’s first meeting:

“But Billy,” Lucifer says. “It’s not like people say. It’s not all Hieronymus Bosch creatures and torture chambers. There aren’t saints looking down on you from above, enjoying the perfection of their beatitude by jerking off to the punishment of the damned.”

Billy raises his head out of his hands. “People say that?” he asks.

“Aquinas said that,” Lucifer says. A hitherto unnoticed bass note in his voice seems to subtly double, and his face contorts into an expression of what appears to be genuine anger. “That fat fuck.”

“Aquinas said ‘jerking off?’” Billy asks, a little spooked. This is the first time Billy’s seen an expression on Lucifer’s face that doesn’t look like it was learned from some kind of demonic field guide to human emotions, and he finds himself hoping that it’ll go away quickly.

“He didn’t say jerking off,” Lucifer concedes. “But he implied it.” His expression goes blank again.

I have few real critiques of this book – it’s an incredibly enjoyable read. There’s a small logic error that no one probably notices except me (editors don’t have an off switch), and my only other complaint is a minor one about pacing. The plot line is introduced into the story early on, as it should be. And then we spend quite a bit of time loafing about in Billy’s head, fretting over things, doubting himself, rolling the decision about Satan around in his head, moping about his girl, etc. Billy’s self-inflicted mannerisms are part of what makes him interesting, but the plot itself doesn’t really make another noticeable appearance until nearly the halfway mark. Bushnell has done a great job of making sure many elements in this loafing period get tied into things later and that everything is relevant, but it’s still just a little too much after a while. It’s a minor instance of having a “soggy middle,” but thankfully doesn’t drag the book to its knees. But! Despite this, if you can get through Billy dragging his feet through the sand for a bit (which does actually characterize him quite well), the book then opens up into a fabulous rise of action that truly continues to get more and more bizarre, as I had hoped it would. It’s a book that gets you excited to see how all the weird, seemingly unconnected elements are going to be tied together in the end.

It’s rare to find a book that validates itself solely because of the title, but the collision of magic, relationship problems, deities, best friends, mythological creatures, world destruction, and a few existential crises do make for an awesomely weird blend. It’s a book riddled with hellfire, metacognition, questions everyone has but never asks, a skirt-flash of the speculative and bizarre, and a hefty dose of highbrow snark. It’s a bit like one of those prank grab bags with a mystery item inside. Will it be something soft? Something gooey? Something that bites? You won’t know until you stick your hand in.