I am interested in poetry as an alternative version of history, with history as an understanding of events as they happened, and also as the space of reflection beyond their happening. Poems, when standing in the space of history, cause the reader to take a sharp breath, to consider, to see.

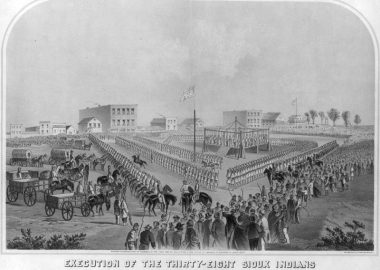

This versioning can take the form of a sweeping, somber brush or the tiniest measuring spoon of truth. One stunning example of this is David Faldet’s poem “Violation,” appearing in The 2RiverView 18.3, Spring 2014. This account of the Dakota War of 1862 renders a relatively unfamiliar period of American history with both that brush and that spoon.

A small amount of research on this event revealed the exploitation of a group of Santee Dakota, a narrative of starvation and retaliation that resulted in the events depicted in Faldet’s work.

At first, the piece’s tone is factual, deliberate, steadied, one of reportage:

When, in the work of December 1862,

Lincoln decided which of 303 death

sentences to commute and who must die

he began with the Dakota who had violated

white women. He found only two.

The tone and the poem’s sound turns to despair, with soft consonants crowding against one another: “These and 36 more he hanged/the rest locked in dark cells.” It continues into a space of forced migration (“[t]housands more fled north and west”), of suffering (“606 were boys and girls, 536 were women”), and finally of an unconscionable variety of human commerce at the hands of white soldiers (“treated their wombs like latrines/in trade for the coins/that could feed the children.”)

When I read this poem I was reminded immediately of Carolyn Forché’s 1979 poem “The Visitor,” the narrative of a condemned man, Francisco, with the final line, as a single-line stanza: “There is nothing one man will not do to another.”

Even with its solitary line of narrative in the latter poem, there are parallels to Faldet’s work in the way that history is recorded secretly and with silent steps, the poet an unseen observer with a sharp pen full of tears.

Forché’s line stays with me even as I read Faldet’s depiction of history, in all its shame and pain, in its meager recompenses and inhumanity. One could use an artist’s brush to paint an idea that the existence of poetry of historical account is tribute or indictment; and perhaps this is true. But for those souls whom the poems memorialize – or perhaps, not so grandiosely – reveal, the true essence is in the careful narrative attention paid to the forced marching of feet from a homeland, or to damp walls felt in darkness, as humanity’s experience and greater, less humane forces collide.

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://minotaursspotlight.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/rose_koch_133.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Rosemarie Koch earned her MFA in Poetry from Arcadia University in 2013 – the culmination of a lifelong dream. For her, poetry is an art form that crosses all forms, and is also a great source of joy – both reading it and writing it. She has recited Hopkins’ “Windhover” at many poetic and non-poetic gatherings, regards William Blake and Emily Dickinson as close personal friends, and finds poetry in everything she hears and sees. Her work with Minotaur’s Spotlight is an extension of her love of verse. [/author_info] [/author]